Modern life vs. your back: Win the fight

If you're among the 31 million Americans with an aching back, here's an important message from your spine: Stop hunching! Get that bowling ball out of your purse, backpack or other tote; put out that cigarette; and change positions frequently.

New research confirms that modern life habits are a major trigger for the most common kind of back pain -- not the type caused by arthritis or a major disease, but back pain that's linked to stuff you do every day that pushes, pulls, bends and torques your spine.

Do you have text neck?

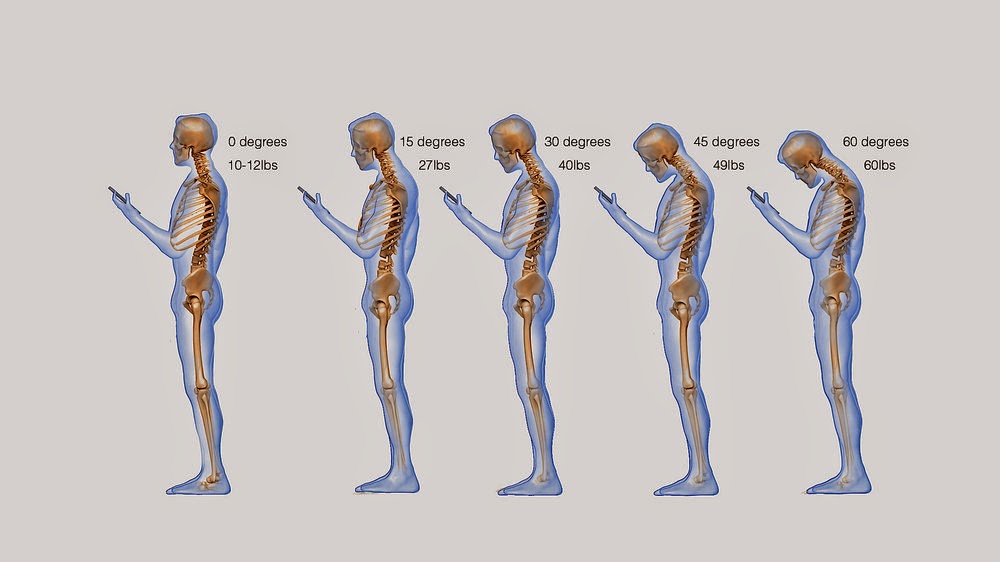

A brand-new report from the New York Spine Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine center has identified "text neck" -- bending your head down to check your messages -- as a major source of chronic back pain. That's because your head weighs about 10-12 pounds, a weight your spine and the muscles that support it can manage easily when you stand up straight. Tilt about 15 degrees (the amount you might bend your neck to see if you have a text) and the load on your upper spine more than doubles, to 27 pounds. As you tilt further downward, the weight increases. It hits 40 pounds at a 30-degree tilt (about how far you'd bend your neck to read the tiny print on your screen) and a whopping 60 pounds at 60 degrees (bending your neck down far enough to feel the pull in your shoulders). That's gotta hurt, and it does.

That bend distorts the natural curve of your back, leading to inflammation and "wear, tear, degeneration and possibly surgeries." That's important news for America's 58 million-plus smartphone users, who spend up to four hours a day hunched over their tiny screens. That adds up to over 1,000 hours of extra spinal stress per year.

Protect your back: Hold your phone up higher when reading and sending messages. And avoid other hazards that throw your spine off-kilter, like heavy purses and backpacks, and sitting on a thick wallet in your back pocket. All of these knock your spine to one side. Lighten the purse or backpack, and keep your wallet to a quarter inch thick or less (keep bills in your front pocket and carry fewer credit cards).

Smokin' spine pain

A tobacco habit triples your risk for back pain, says a new study from Northwestern University. We already knew that cigarettes boosted odds for backaches, but this report reveals just how much damage they can do -- and how. Brain scans of 160 people with back pain show that smoking strengthens the connection between two parts of the brain that convert temporary pain into chronic pain. Pain relievers dull the ache but don't put a dent in this superhighway to agony.

What works: Kicking the butts. For smokers who quit during the study, this connection became less active and more like that of nonsmokers. That's good news, because it means their risk for chronic pain dropped, too.

Protect your back: Quit smoking. It's never too late to try. Don't be discouraged by relapses; just try again. Find out about the best way to become an ex-smoker at sharecare.com.

Sitting, standing, stress

If you're on your feet all day, you probably already know that prolonged standing can do a number on your spine, but so can prolonged sitting at a desk. Doing either one the wrong way puts extra pressure on your spine's stack of discs and surrounding muscles.

Protect your back: Supportive footwear can help if you stand for much of the day. Taking brief breaks to sit or move around works, too. If your job keeps you at your desk, get up every 20-30 minutes, walk around and stretch for 90 seconds. Make sure your desk chair supports your lower back and that you can keep your feet flat on the floor, with your knees at hip level or a little lower. Use a headset instead of tucking your phone between your ear and shoulder, too.

Dr. Mehmet Oz, is host of "The Dr. Oz Show" and Dr. Mike Roizen is chief medical officer at the Cleveland Clinic Wellness Institute. Distributed by King Features Syndicate Inc.

Read more here information on back pain visit www.spechtpt.com